EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This post is an overview of research conducted by external researchers (see bibliography) on affordable housing barriers. As such, it does not necessarily represent the opinions of Pioneer Valley Habitat for Humanity, but is provided for educational purposes.

Rural communities, including those of Hampshire and Franklin counties of Massachusetts, experience a shortage of affordable housing options. A lack of affordable housing can be seen as symptomatic of a larger feedback loop of poverty in rural communities. This cycle includes lack of employment opportunities, a minimum wage that has not risen with inflation, and high transportation costs due to lack of public transportation. With one of the highest housing price rates in the country, it is not easy for developers to see a return on their investment in building affordable housing options in Massachusetts (Carston 2014).

Many outdated building restrictions contribute to affordable housing barriers, and not all of the policies set in place to remedy these barriers have been effective (Page 2006). While some regulations are necessary to ensure the health and safety of residents, other regulations are more difficult to differentiate as necessary or not (Schill 2004).

Luckily, there are a number of potential solutions to affordable housing barriers. These include creating mixed-income developments, forming interdisciplinary research coalitions, increasing uniformity in zoning and building code policies across the Commonwealth, taking advantage of opportunities to work with community land trusts, and updating incentives from the state and federal level for municipalities to remove affordable housing barriers (Carston 2014, Oster 1977, Schill 2004). By implementing many of these solutions, our community can work together to create opportunities for more access to affordable housing. —————————————————————————————————————————————————–

BACKGROUND

A shortage of affordable housing options has been plaguing rural communities, including those in Hampshire and Franklin counties of Massachusetts, for quite some time. Affordable housing shortages can be seen as symptomatic of a larger positive feedback loop of poverty in rural communities. This cycle includes lack of employment opportunities, a minimum wage that has not risen with inflation, and high transportation costs due to lack of public transportation (Carston 2014).

Most of the funding and policy efforts to create more affordable housing options have been focused on the Greater Boston area instead of on rural communities in western Massachusetts, who are arguably the communities in our Commonwealth that are struggling the most with this shortage. With one of the highest housing price rates in the country, it is not easy for developers to see a return on their investment in building affordable housing options in Massachusetts (Carston 2014).

Due to lack of available jobs, many rural populations are increasing in percentage of retired residents, as younger professionals must leave the area to find viable employment opportunities to support their families. As the average population ages, more accessible housing for those with physical limitations is needed, yet the costs of these accessible homes often exceeds the budget of those on a fixed income. A decline in the percentage of younger residents with families also creates a more stagnant local economy, leading to a decline in local business stimulation and success (Carston 2014).

POLICIES CONTRIBUTING TO LACK OF AFFORDABLE HOUSING

Many policies and building codes contribute to affordable housing barriers. One such regulatory issue is restrictions on land use. A 1962 Supreme Court case, Euclid v. Ambler Realty, decided zoning is a constitutional right of police power to prevent nuisances. This decision trickled down into stricter zoning requirements on land use regulation (Schill 2004). Zoning code requirements exist in many communities for minimum building size, large lawn frontage, minimum lot size, and deed restrictions that limit the affordability of subdivision housing. Land use restrictions such as these can create barriers to affordable housing access (Green Built Home Program of the Wisconsin Environmental Initiative).

Typically, when housing demand increases, labor demands increase proportionally. Communities with higher construction prices and higher housing demand are more likely to create innovative solutions to typical building codes. The power of unions in a community may also influence what cost reducing innovations are accepted (Oster 1977). Building materials manufacturer lobbying may result in overly cautious and expensive building requirements that go far beyond the minimum requirements to ensure health and safety of residents (Schill 2004).

Additionally, communities are under pressure to raise taxes for public service funding, so policies are often implemented that favor higher-cost housing development. While some regulations are necessary to ensure the health and safety of residents, such as fire prevention, air quality, and sanitation, other regulations are more difficult to differentiate as necessary or not (Schill 2004).

Delays on development can stem from administrative roadblocks, such as the lengthy application and decision making process for rezoning, which increases the time required to receive a building permit, and is positively correlated with higher land and housing prices. Deregulation is controversial as it may lead to degradation of the surrounding environment, which poses public health risks in addition to risks to local flora and fauna (Schill 2004).

CURRENT POLICIES AIMED AT ALLEVIATING BARRIERS

Well aware of the crisis in the lack of affordable housing access, various policies and funding opportunities have been set up at local, state, and federal government levels. Some policies have proved more effective than others. Chapter 40B, The Comprehensive Permit Law (1969) is one such effective policy. It created 22,000 housing units for residents making less than eighty percent of area median incomes. Chapter 40B streamlined the permitting process for affordable housing developers, and allowed for densities higher than usual zoning rules permit (Page 2006).

Another policy aimed at combatting the lack of housing access for lower-income families is Chapter 40R, Smart Growth Zoning Districts (2004). This regulation encourages the overlay of zoning districts so that developers can follow codes of either district’s zoning requirements. It also provides incentive payments to towns from the state to make twenty percent of units affordable housing options in developments of twelve or more units. Accompanying this regulation is Chapter 40S, which was set up to provide educational funding to communities with these smart growth zoning districts. However, these policies have been ineffective as communities outside of the greater Boston area have formed smart growth districts yet, despite a push from the Massachusetts legislature (Special Senate Committee on Housing, 2016).

Local levels of government have created inclusionary zoning regulations, which have had limited effectiveness. These regulations incentivize developers to include affordable housing in market-rate residential developments, and maintain affordability of the homes through deed restrictions. Density bonuses are given to developers to offset affordable unit development costs. Though adopted by more than one hundred communities in the state, inclusionary zoning has not led to the development of many affordable housing units thus far (Page 2006).

Another policy action is to encourage brownfields redevelopment, or the remediation of abandoned and polluted sites, to increase the availability of potential housing lot sites and stimulate economic development with remediation job opportunities (Page 2006).

A CONTROVERSIAL SOLUTION: MIXED-INCOME HOUSING BENEFITS AND ROADBLOCKS

Mixed income housing offers a variety of benefits within communities. These include better educational opportunities for children of lower-income families and creating diverse neighborhoods. In addition, mixed-income communities allow for shorter commutes to work for lower-income families, thus providing for lower turnover rates at local jobs. They also allow public servants such as teachers and social workers, who cannot afford higher-income neighborhoods, to live within the communities where they work (Green Built Home Program of the Wisconsin Environmental Initiative).

Not-In-My-Backyard (NIMBY) sentiments, as well as racism and other discriminatory belief systems create barriers to achieving the benefits of mixed-income housing. Wealthier communities may express prejudiced fears of lower income residents coming into their communities, asserting that this may increase crime rates (Green Built Home Program of the Wisconsin Environmental Initiative).

But mixed-income housing is in fact one way to combat and break down these systemic fears. It exposes residents to a community of people of many different cultures, ethnicities, races, and religions, thus helping to foster greater acceptance and appreciation for differences (Green Built Home Program of the Wisconsin Environmental Initiative).

POTENTIAL POLICY SOLUTIONS

Luckily, there are a number of potential policy solutions to affordable housing barriers. Communities could aim to create coalitions and policies that take a more interdisciplinary approach, instead of treating individual symptoms of a larger systemic problem. Massachusetts could consider creating either public or private coalitions to address rural policy making, as states including Vermont, Maryland, and Pennsylvania have done. Research and policy could take a multi-faceted approach to addressing barriers to affordable housing access, including educational improvements, public transportation expansion, economic development incentives, and expanded technology and healthcare access (Carsten 2014).

Insurance in place of public regulation could potentially create a market of optional insurance policies available to sellers or buyers of used homes, functioning similarly to product warranties. Additionally, increasing building code uniformity across communities may lower the cost of construction (Oster 1977).

“Smart codes” for rehabilitation projects cater building code requirements to renovation projects that differ from new development requirements and can greatly reduce renovation costs. Federal administration could require municipalities that receive federal assistance funding to report annually on how they are working to reduce regulatory barriers to affordable housing development. Municipalities could also be mandated to include affordable housing as part of all market-rate developments (Schill 2004).

More thorough research on local regulatory practices across regions could be conducted so that Massachusetts can work towards creating uniformity in building codes throughout the state (Schill 2004). Distribution of educational materials, created by these coalitions, to home buyers and local community planning authorities would help prevent communities from imposing unnecessary land use regulations, and allow buyers to be better informed while negotiating with developers (Green Built Home Program of the Wisconsin Environmental Initiative).

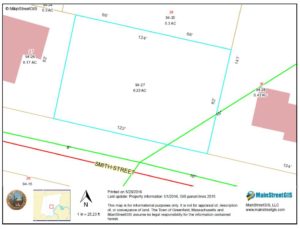

Community land trusts can also help reduce the cost of buying a home. Pioneer Valley Habitat for Humanity is working with the Amherst Community Land Trust on its newest project in North Amherst so that the homebuyers only have to cover the cost of buying the home and can lease the use of the land (Green Built Home Program of the Wisconsin Environmental Initiative). This also allows the land to remain in the community trust to prevent less-affordable future construction, and preserve important ecological functions afforded by maintaining some undeveloped land.

By implementing many of these solutions, our community can work together to create opportunities for more access to affordable housing.

Works Cited

Carsten, S.; Farrel, R.; Lodi, R.; Clark, C. Massachusetts Housing Partnership. (2014). White Paper on Rural Housing Issues in Massachusetts: Findings of the Rural Initiative and Recommendations.

Green Built Home Program of the Wisconsin Environmental Initiative. No date. The Green Built Way to Affordable Housing: A Series of Goals and Strategies for the Effective Greening of Affordable Housing. White paper. Madison, Wisconsin.

Oster, S.M.; Quiqley, J.M. (1977). Regulatory Barriers to the Diffusion of Innovation: Some Evidence from Building Codes. The Bell Journal of Economics, Vol. 8(No. 2), 361-377. Retrieved from: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0361-915X%28197723%298%3A2%3C361%3ARBTTDO%3E2.0.CO%3B2-W

Page, M.; Makker, K. (2006). Housing Within Reach: Innovations in Affordable Housing Design. Conference Program. University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Schill, M. H. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. (2004). Regulations and Housing Development: What We Know and What We Need to Know. Conference on Regulatory Barriers to Affordable Housing. New York University.

Special Senate Committee on Housing. (2016). Facing Massachusetts’ Housing Crisis. (Report SD.2473). Boston, MA: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Pioneer Valley Habitat for Humanity has built over 37 homes in Hampshire and Franklin Counties since 1989. For the benefit of future volunteers, staff and community members who want to build their own home – we are starting this blog on the development process for a single family house in Greenfield, MA. Most people think about the framing of the walls as the start of construction – but planning a project often starts months or years before the first hammer is raised.

Pioneer Valley Habitat for Humanity has built over 37 homes in Hampshire and Franklin Counties since 1989. For the benefit of future volunteers, staff and community members who want to build their own home – we are starting this blog on the development process for a single family house in Greenfield, MA. Most people think about the framing of the walls as the start of construction – but planning a project often starts months or years before the first hammer is raised.